Violent Us Crime Drops Again Reaches 1970s Level Fb

Facts matter: Sign upwards for the costless Female parent Jones Daily newsletter. Support our nonprofit reporting. Subscribe to our print magazine.

When Rudy Giuliani ran for mayor of New York Urban center in 1993, he campaigned on a platform of bringing downward crime and making the city rubber over again. It was a comfy position for a old federal prosecutor with a tough-guy image, but it was more than mere posturing. Since 1960, rape rates had nearly quadrupled, murder had quintupled, and robbery had grown fourteenfold. New Yorkers felt like they lived in a city nether siege.

Throughout the campaign, Giuliani embraced a theory of criminal offence fighting called "cleaved windows," popularized a decade earlier by James Q. Wilson and George 50. Kelling in an influential article in The Atlantic. "If a window in a edifice is broken and is left unrepaired," they observed, "all the residue of the windows will soon exist cleaved." Then too, tolerance of small crimes would create a vicious cycle ending with unabridged neighborhoods turning into war zones. But if yous croaky downwardly on small crimes, bigger crimes would drib also.

Giuliani won the election, and he made skillful on his crime-fighting promises past selecting Boston police chief Bill Bratton equally the NYPD's new commissioner. Bratton had made his reputation as head of the New York City Transit Law, where he aggressively applied broken-windows policing to turnstile jumpers and vagrants in subway stations. With Giuliani's eager back up, he began applying the same lessons to the entire city, going later panhandlers, drunks, drug pushers, and the metropolis's hated squeegee men. And more: He decentralized police operations and gave precinct commanders more control, keeping them accountable with a pioneering system chosen CompStat that tracked offense hot spots in existent time.

The results were dramatic. In 1996, the New York Times reported that criminal offence had plunged for the third straight year, the sharpest drib since the cease of Prohibition. Since 1993, rape rates had dropped 17 percent, assault 27 percent, robbery 42 percentage, and murder an astonishing 49 percent. Giuliani was on his way to condign America's Mayor and Bratton was on the encompass of Time. Information technology was a remarkable public policy victory.

But even more than remarkable is what happened adjacent. Shortly subsequently Bratton's star turn, political scientist John DiIulio warned that the repeat of the baby boom would soon produce a demographic bulge of millions of young males that he famously dubbed "juvenile super-predators." Other criminologists nodded along. Simply even though the demographic bulge came right on schedule, criminal offense continued to driblet. And driblet. And drib. Past 2010, violent criminal offense rates in New York Urban center had plunged 75 percent from their peak in the early on '90s.

All in all, information technology seemed to be a story with a happy ending, a triumph for Wilson and Kelling's theory and Giuliani and Bratton'due south practice. And still, doubts remained. For 1 thing, violent offense actually peaked in New York City in 1990, four years before the Giuliani-Bratton era. By the time they took office, information technology had already dropped 12 per centum.

2d, and far more puzzling, information technology'due south non merely New York that has seen a large drop in criminal offence. In city after urban center, violent crime peaked in the early on '90s and then began a steady and spectacular reject. Washington, DC, didn't have either Giuliani or Bratton, but its violent crime charge per unit has dropped 58 percentage since its superlative. Dallas' has fallen 70 percent. Newark: 74 percentage. Los Angeles: 78 percent.

There must be more than going on here than simply a alter in policing tactics in ane urban center. But what?

Analogy: Gérard DuBois

There are, information technology turns out, plenty of theories. When I started research for this story, I worked my way through a pair of thick criminology tomes. 1 chapter regaled me with the "exciting possibility" that it'southward mostly a affair of economics: Crime goes down when the economy is booming and goes up when it's in a slump. Unfortunately, the theory doesn't seem to hold h2o—for case, crime rates have continued to drop recently despite our prolonged downturn.

Some other affiliate suggested that criminal offence drops in big cities were more often than not a reflection of the crack epidemic of the '80s finally burning itself out. A trio of authors identified iii major "drug eras" in New York City, the beginning dominated by heroin, which produced limited violence, and the 2nd past crack, which generated spectacular levels of information technology. In the early '90s, these researchers proposed, the children of CrackGen switched to marijuana, choosing a less violent and more law-abiding lifestyle. As they did, crime rates in New York and other cities went down.

Another chapter told a story of demographics: Equally the number of young men increases, then does law-breaking. Unfortunately for this theory, the number of young men increased during the '90s, but crime dropped anyhow.

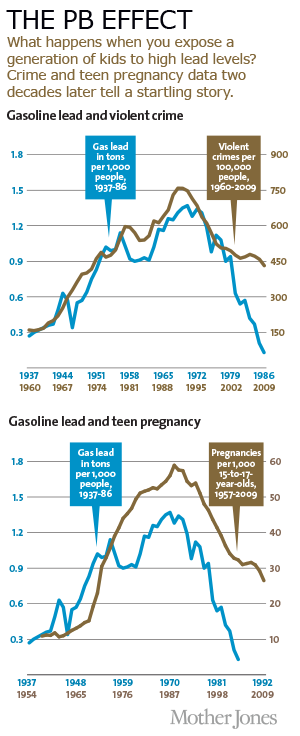

Top: Rick Nevin, USGS, DOJ; Lesser: Rick Nevin, Guttmacher Plant, CDC

In that location were chapters in my tomes on the effect of prison house expansion. On guns and gun control. On family unit. On race. On parole and probation. On the raw number of constabulary officers. Information technology seemed as if everyone had a pet theory. In 1999, economist Steven Levitt, afterward famous as the coauthor of Freakonomics, teamed upwards with John Donohue to suggest that criminal offense dropped because of Roe v. Wade; legalized abortion, they argued, led to fewer unwanted babies, which meant fewer maladjusted and tearing immature men ii decades later.

But there's a problem common to all of these theories: It's hard to tease out actual proof. Maybe the end of the crack epidemic contributed to a decline in inner-city crime, but so once again, maybe it was really the outcome of increased incarceration, more than cops on the beat, broken-windows policing, and a rise in ballgame rates twenty years earlier. Afterwards all, they all happened at the same time.

To accost this trouble, the field of econometrics gives researchers an enormous toolbox of sophisticated statistical techniques. Only, notes statistician and conservative commentator Jim Manzi in his recent volume Uncontrolled, econometrics consistently fails to explain almost of the variation in criminal offence rates. After reviewing 122 known field tests, Manzi found that just 20 percent demonstrated positive results for specific criminal offence-fighting strategies, and none of those positive results were replicated in follow-upward studies.

So we're back to foursquare ane. More prisons might assistance control crime, more cops might help, and amend policing might assistance. But the evidence is thin for any of these as the master cause. What are we missing?

Experts often suggest that crime resembles an epidemic. Merely what kind? Karl Smith, a professor of public economics and government at the University of N Carolina-Chapel Loma, has a adept rule of pollex for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along lines of communication, he says, the cause is information. Call up Bieber Fever. If information technology travels along major transportation routes, the cause is microbial. Think flu. If it spreads out similar a fan, the cause is an insect. Retrieve malaria. Just if it'southward everywhere, all at once—equally both the rising of crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of law-breaking in the '90s seemed to exist—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What molecule could be responsible for a steep and sudden decline in tearing criminal offense?

Well, here's one possibility: Lead(CH2CH3)four.

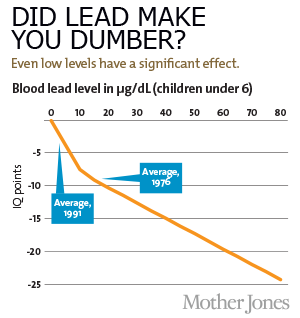

Rick Nevin/CDC

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant working for the US Department of Housing and Urban Evolution on the costs and benefits of removing lead paint from old houses. This has been a topic of intense report because of the growing torso of research linking atomic number 82 exposure in small children with a whole raft of complications after in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity, behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

Merely as Nevin was working on that assignment, his customer suggested they might exist missing something. A recent report had suggested a link between childhood lead exposure and juvenile delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead exposure had an result on violent offense too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns out, wasn't paint. Information technology was leaded gasoline. And if you lot nautical chart the ascension and autumn of atmospheric lead caused past the ascension and fall of leaded gasoline consumption, you go a pretty elementary upside-down U: Atomic number 82 emissions from tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period. Then, as unleaded gasoline began to supercede leaded gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Gasoline pb may explain equally much as xc per centum of the ascension and fall of violent crime over the past one-half century.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the aforementioned upside-down U pattern. The only affair different was the time period: Offense rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the '80s, then began dropping steadily starting in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily identical, but were offset past about 20 years.

So Nevin dove in further, excavation upward detailed data on atomic number 82 emissions and crime rates to encounter if the similarity of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned out to be even better: In a 2000 paper (PDF) he ended that if you add together a lag time of 23 years, pb emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of the variation in trigger-happy crime in America. Toddlers who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and '50s really were more likely to become violent criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetraethyl atomic number 82, the gasoline additive invented by General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking and pinging in high-operation engines. Equally auto sales boomed afterwards Earth War 2, and drivers in powerful new cars increasingly asked service station attendants to "fill 'er up with ethyl," they were unwittingly creating a criminal offence moving ridge two decades later.

It was an exciting conjecture, and it prompted an immediate wave of…nothing. Nevin'due south paper was almost completely ignored, and in one sense information technology's easy to run into why—Nevin is an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper was published in Environmental Research, not a journal with a large readership in the criminology community. What's more than, a single correlation betwixt 2 curves isn't all that impressive, econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose in the postwar period too, and and so declined in the '80s and '90s. Lots of things follow a pattern like that. Then no matter how adept the fit, if y'all only take a single correlation it might simply be a coincidence. You lot need to do something more than to establish causality.

Every bit information technology turns out, however, a few hundred miles north someone was doing only that. In the tardily '90s, Jessica Wolpaw Reyes was a graduate student at Harvard casting effectually for a dissertation topic that eventually became a study she published in 2007 every bit a public health policy professor at Amherst. "I learned virtually lead considering I was meaning and living in former housing in Harvard Square," she told me, and after attention a talk where time to come Freakonomics star Levitt outlined his abortion/criminal offence theory, she started thinking about pb and criminal offence. Although the association seemed plausible, she wanted to notice out whether increased lead exposure caused increases in criminal offense. Just how?

In states where consumption of leaded gasoline declined slowly, crime declined slowly. Where it declined quickly, criminal offense declined speedily.

The answer, it turned out, involved "several months of common cold calling" to find lead emissions data at the state level. During the '70s and '80s, the introduction of the catalytic converter, combined with increasingly stringent Environmental Protection Agency rules, steadily reduced the amount of leaded gasoline used in America, but Reyes discovered that this reduction wasn't uniform. In fact, use of leaded gasoline varied widely among states, and this gave Reyes the opening she needed. If childhood lead exposure actually did produce criminal behavior in adults, you'd expect that in states where consumption of leaded gasoline declined slowly, crime would reject slowly besides. Conversely, in states where it declined quickly, law-breaking would decline quickly. And that'southward exactly what she institute.

Meanwhile, Nevin had kept busy also, and in 2007 he published a new paper looking at crime trends effectually the world (PDF). This way, he could make sure the close match he'd found betwixt the lead curve and the crime curve wasn't just a coincidence. Sure, maybe the real culprit in the United States was something else happening at the verbal same time, but what are the odds of that same something happening at several different times in several unlike countries?

Nevin collected lead information and offense data for Australia and found a close lucifer. Ditto for Canada. And Not bad U.k. and Finland and France and Italy and New Zealand and Westward Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other astonishingly well. When I spoke to Nevin near this, I asked him if he had ever found a country that didn't fit the theory. "No," he replied. "Not one."

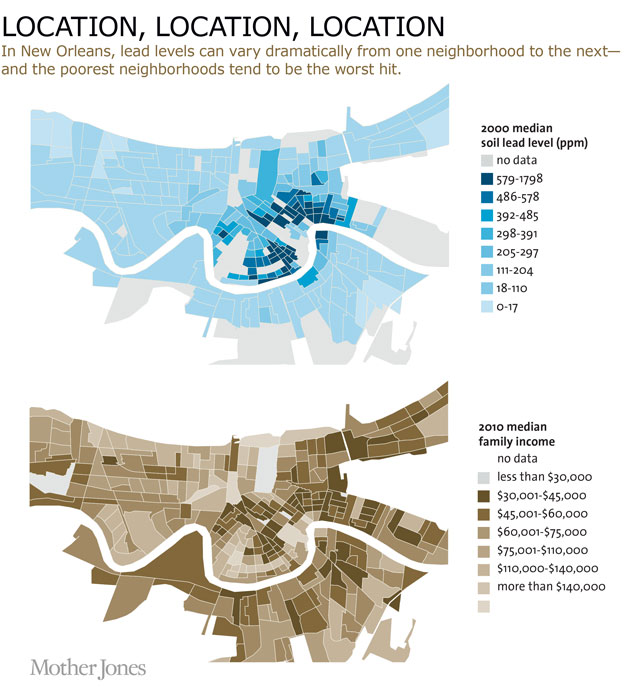

Just this yr, Tulane University researcher Howard Mielke published a newspaper with demographer Sammy Zahran on the correlation of pb and crime at the city level. They studied six U.s. cities that had both proficient criminal offense data and practiced lead data going dorsum to the '50s, and they found a practiced fit in every single ane. In fact, Mielke has fifty-fifty studied lead concentrations at the neighborhood level in New Orleans and shared his maps with the local police. "When they overlay them with crime maps," he told me, "they realize they match upwardly."

Put all this together and you lot have an astonishing body of evidence. We now have studies at the international level, the national level, the country level, the city level, and fifty-fifty the individual level. Groups of children have been followed from the womb to machismo, and college babyhood claret lead levels are consistently associated with higher adult arrest rates for violent crimes. All of these studies tell the same story: Gasoline pb is responsible for a proficient share of the ascension and fall of violent crime over the by half century.

When differences of atmospheric lead density between big and small-scale cities largely went abroad, and then did the difference in murder rates.

Like many expert theories, the gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain some things we might not have realized even needed explaining. For example, murder rates have e'er been higher in large cities than in towns and small cities. We're so used to this that it seems unsurprising, only Nevin points out that information technology might actually take a surprising explanation—because large cities have lots of cars in a small-scale area, they as well had high densities of atmospheric lead during the postwar era. But every bit lead levels in gasoline decreased, the differences betwixt big and minor cities largely went away. And guess what? The difference in murder rates went away too. Today, homicide rates are like in cities of all sizes. It may be that trigger-happy crime isn't an inevitable consequence of being a large city after all.

The gasoline lead story has another virtue too: It'southward the only hypothesis that persuasively explains both the rise of offense in the '60s and '70s and its fall beginning in the '90s. Two other theories—the infant boom demographic burl and the drug explosion of the '60s—at least have the potential to explicate both, but neither i fully fits the known data. Only gasoline lead, with its dramatic ascension and fall following World War Ii, can explicate the every bit dramatic ascension and fall in violent crime.

If econometric studies were all there were to the story of lead, you'd be justified in remaining skeptical no thing how proficient the statistics await. Even when researchers do their best—decision-making for economic growth, welfare payments, race, income, education level, and everything else they tin think of—it'southward ever possible that something they haven't thought of is however lurking in the background. But there's another reason to take the atomic number 82 hypothesis seriously, and it might be the most compelling 1 of all: Neurological research is demonstrating that lead'south effects are even more appalling, more permanent, and appear at far lower levels than we e'er idea. For starters, information technology turns out that childhood lead exposure at about whatever level can seriously and permanently reduce IQ. Blood atomic number 82 levels are measured in micrograms per deciliter, and levels once believed safety—65 μg/dL, then 25, then 15, then 10—are now known to crusade serious damage. The EPA now says flatly that there is "no demonstrated safe concentration of atomic number 82 in blood," and it turns out that even levels nether 10 μg/dL can reduce IQ by as much as seven points. An estimated two.5 per centum of children nationwide accept atomic number 82 levels above 5 μg/dL.

But we now know that pb's effects make it beyond just IQ. Non only does lead promote apoptosis, or cell death, in the brain, but the chemical element is also chemically similar to calcium. When it settles in cognitive tissue, it prevents calcium ions from doing their job, something that causes physical damage to the developing brain that persists into machismo.

Only in the last few years have we begun to understand exactly what furnishings this has. A team of researchers at the University of Cincinnati has been following a group of 300 children for more than than 30 years and recently performed a series of MRI scans that highlighted the neurological differences betwixt subjects who had high and low exposure to lead during early childhood.

Loftier babyhood exposure damages a function of the brain linked to assailment control. The impact is greater among boys.

One set of scans found that lead exposure is linked to product of the brain's white matter—primarily a substance chosen myelin, which forms an insulating sheath effectually the connections between neurons. Lead exposure degrades both the formation and structure of myelin, and when this happens, says Kim Dietrich, one of the leaders of the imaging studies, "neurons are not communicating effectively." Put simply, the network connections inside the encephalon become both slower and less coordinated.

A second study institute that high exposure to lead during babyhood was linked to a permanent loss of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex—a role of the brain associated with assailment command as well as what psychologists phone call "executive functions": emotional regulation, impulse command, attention, verbal reasoning, and mental flexibility. One way to understand this, says Kim Cecil, some other fellow member of the Cincinnati team, is that lead affects precisely the areas of the brain "that make us most human."

So atomic number 82 is a double whammy: It impairs specific parts of the brain responsible for executive functions and it impairs the communication channels between these parts of the brain. For children like the ones in the Cincinnati written report, who were mostly inner-city kids with plenty of strikes against them already, lead exposure was, in Cecil'due south words, an "additional kicking in the gut." And one more than thing: Although both sexes are affected by lead, the neurological impact turns out to be greater among boys than girls.

Other recent studies link fifty-fifty minuscule blood pb levels with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Even at concentrations well below those usually considered safe—levels still common today—atomic number 82 increases the odds of kids developing ADHD.

In other words, every bit Reyes summarized the show in her newspaper, even moderately high levels of pb exposure are associated with aggressivity, impulsivity, ADHD, and lower IQ. And right there, you lot've practically defined the profile of a violent immature offender.

Needless to say, non every child exposed to lead is destined for a life of crime. Everyone over the age of xl was probably exposed to also much pb during babyhood, and most of us suffered nothing more than a few points of IQ loss. Simply there were plenty of kids already on the margin, and millions of those kids were pushed over the edge from existence merely ho-hum or disruptive to becoming office of a nationwide epidemic of violent criminal offence. Once y'all understand that, it all becomes blindingly obvious. Of grade massive lead exposure amongst children of the postwar era led to larger numbers of violent criminals in the '60s and across. And of course when that lead was removed in the '70s and '80s, the children of that generation lost those artificially heightened violent tendencies.

Constabulary chiefs want to retrieve what they do on a daily basis matters. And it does. But perchance not as much every bit they think.

Just if all of this solves 1 mystery, it shines a loftier-powered klieg light on another: Why has the lead/crime connexion been almost completely ignored in the criminology community? In the two big books I mentioned earlier, one has no mention of atomic number 82 at all and the other has a grand total of two passing references. Nevin calls it "exasperating" that criminal offence researchers haven't seriously engaged with lead, and Reyes told me that although the public health community was interested in her newspaper, criminologists have largely been AWOL. When I asked Sammy Zahran well-nigh the reaction to his paper with Howard Mielke on correlations betwixt lead and criminal offence at the city level, he but sighed. "I don't think criminologists have even read it," he said. All of this jibes with my own reporting. Before he died final year, James Q. Wilson—father of the broken-windows theory, and the dean of the criminology community—had begun to accept that lead probably played a meaningful role in the law-breaking drib of the '90s. But he was apparently an outlier. None of the criminology experts I contacted showed any involvement in the lead hypothesis at all.

Why non? Mark Kleiman, a public policy professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who has studied promising methods of controlling crime, suggests that considering criminologists are basically sociologists, they wait for sociological explanations, not medical ones. My own sense is that interest groups probably play a crucial function: Political conservatives want to arraign the social upheaval of the '60s for the rise in criminal offence that followed. Law unions have reasons for crediting its pass up to an increase in the number of cops. Prison guards like the idea that increased incarceration is the answer. Drug warriors want the story to be virtually drug policy. If the actual answer turns out to be lead poisoning, they all lose a big pillar of support for their pet outcome. And while lead abatement could exist large business for contractors and builders, for some reason their trade groups have never taken it seriously.

More mostly, we all have a deep pale in affirming the ability of deliberate deed. When Reyes once presented her results to a conference of constabulary chiefs, it was, unsurprisingly, a tough sell. "They want to call back that what they do on a daily basis matters," she says. "And it does." But it may not affair every bit much equally they recollect.

So is this all just an interesting history lesson? After all, leaded gasoline has been banned since 1996, and so even if it had a major touch on violent crime during the 20th century, there's null more to be washed on that forepart. Correct?

Wrong. As it turns out, tetraethyl atomic number 82 is like a zombie that refuses to die. Our cars may be lead-gratuitous today, but they spent more than 50 years spewing lead from their tailpipes, and all that lead had to go somewhere. And it did: It settled permanently into the soil that we walk on, grow our food in, and allow our kids play around.

That'southward particularly true in the inner cores of big cities, which had the highest density of automobile traffic. Mielke has been studying pb in soil for years, focusing most of his attending on his hometown of New Orleans, and he's measured x separate census tracts there with atomic number 82 levels over 1,000 parts per million.

To get a sense of what this ways, you accept to wait at how soil levels of pb typically correlate with blood levels, which are what really thing. Mielke has studied this in New Orleans, and it turns out that the numbers go up very fast fifty-fifty at low levels. Children who live in neighborhoods with a soil level of 100 ppm take average claret lead concentrations of 3.8 μg/dL—a level that'south only barely tolerable. At 500 ppm, blood levels get up to 5.ix μg/dL, and at 1,000 ppm they go up to 7.5 μg/dL. These levels are high enough to practice serious damage.

"I know people who have move into gentrified neighborhoods and renovate everything. They create huge hazards for their kids."

Mielke's partner, Sammy Zahran, walked me through a lengthy—and hair-raising—presentation most the upshot that all that old gasoline lead continues to have in New Orleans. The very first slide describes the basic problem: Lead in soil doesn't stay in the soil. Every summertime, similar clockwork, as the weather dries up, all that lead gets kicked dorsum into the atmosphere in a process chosen resuspension. The zombie lead is back to haunt us.

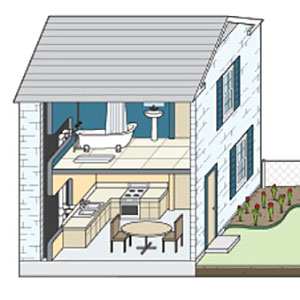

Mark Laidlaw, a doctoral student who has worked with Mielke, explains how this works: People and pets rail pb grit from soil into houses, where it's ingested by small children via manus-to-mouth contact. Ditto for atomic number 82 dust generated by old paint inside houses. This dust cocktail is where most lead exposure today comes from.

Paint hasn't played a big office in our story and then far, only that'south merely considering it didn't play a large part in the rise of crime in the postwar era and its subsequent autumn. Unlike gasoline atomic number 82, lead paint was a adequately uniform problem during this period, producing higher overall lead levels, especially in inner cities, just non changing radically over time. (It'south a different story with the beginning part of the 20th century, when utilize of atomic number 82 paint did rise and then fall somewhat dramatically. Sure enough, murder rates rose and fell in tandem.)

And just like gasoline lead, a lot of that lead in old housing is still around. Lead paint chips flaking off of walls are ane obvious source of lead exposure, but an fifty-fifty bigger one, says Rick Nevin, are old windows. Their friction surfaces generate lots of dust as they're opened and closed. (Other sources—lead pipes and solder, leaded fuel used in private aviation, and lead smelters—business relationship for far less.)

We know that the cost of all this lead is staggering, not merely in lower IQs, delayed development, and other health issues, but in increased rates of violent crime as well. And so why has information technology been and so hard to go it taken seriously?

There are several reasons. One of them was put bluntly by Herbert Needleman, one of the pioneers of research into the effect of lead on behavior. A few years ago, a reporter from the Baltimore City Paper asked him why so little progress had been fabricated recently on combating the lead-poisoning problem. "Number one," he said without hesitation, "it'southward a black trouble." But it turns out that this is an outdated idea. Although it's true that atomic number 82 poisoning affects low-income neighborhoods disproportionately, it affects plenty of heart-grade and rich neighborhoods too. "Information technology's not just a poor-inner-city-child problem anymore," Nevin says. "I know people who take moved into gentrified neighborhoods and immediately renovate everything. And they create huge hazards for their kids."

Tamara Rubin, who lives in a middle-class neighborhood in Portland, Oregon, learned this the difficult way when 2 of her children developed pb poisoning later some routine home improvement in 2005. A few years later, Rubin started the Lead Safe America Foundation, which advocates for lead abatement and atomic number 82 testing. Her message: If y'all live in an old neighborhood or an one-time house, go tested. And if you renovate, practise information technology safely.

Another reason that atomic number 82 doesn't get the attending it deserves is that also many people think the problem was solved years ago. They don't realize how much lead is yet hanging around, and they don't empathize merely how much it costs united states of america.

Information technology's difficult to put business firm numbers to the costs and benefits of atomic number 82 abatement. Simply for a rough idea, let's kickoff with the two biggest costs. Nevin estimates that there are perhaps sixteen million pre-1960 houses with lead-painted windows, and replacing them all would cost something similar $x billion per year over 20 years. Soil cleanup in the hardest-striking urban neighborhoods is tougher to get a handle on, with estimates ranging from $2 to $36 per square foot. A crude extrapolation from Mielke's approximate to clean up New Orleans suggests that a nationwide program might toll another $ten billion per twelvemonth.

We can either become rid of the remaining atomic number 82, or we tin can wait twenty years and so lock up all the kids who've turned into criminals.

Then in round numbers that's about $20 billion per year for two decades. But the benefits would be huge. Let's just accept a look at the two biggest ones. By Mielke and Zahran's estimates, if we adopted the soil standard of a state like Norway (roughly 100 ppm or less), information technology would bring about $30 billion in annual returns from the cognitive benefits solitary (higher IQs, and the resulting higher lifetime earnings). Cleaning up one-time windows might double this. And tearing law-breaking reduction would exist an fifty-fifty bigger benefit. Estimates hither are even more difficult, but Mark Kleiman suggests that a 10 per centum drop in criminal offence—a goal that seems reasonable if nosotros get serious virtually cleaning up the terminal of our pb problem—could produce benefits as high as $150 billion per yr.

Put this all together and the benefits of lead cleanup could be in the neighborhood of $200 billion per year. In other words, an annual investment of $20 billion for xx years could produce returns of x-to-1 every unmarried year for decades to come. Those are returns that Wall Street hedge funds can just dream of.

There'due south a flip side to this likewise. At the same time that nosotros should reassess the depression level of attention nosotros pay to the remaining hazards from lead, we should probably also reassess the high level of attention nosotros're giving to other policies. Principal among these is the prison-building boom that started in the mid-'70s. As criminal offence scholar William Spelman wrote a few years agone, states have "doubled their prison populations, then doubled them again, increasing their costs by more than than $20 billion per yr"—coin that could accept been usefully spent on a lot of other things. And while some scholars conclude that the prison blast had an effect on crime, contempo enquiry suggests that ascension incarceration rates suffer from diminishing returns: Putting more criminals behind bars is useful upwards to a point, but beyond that nosotros're just locking up more than people without having whatever real impact on criminal offence. What's more, if it's truthful that lead exposure accounts for a big function of the crime decline that we formerly credited to prison expansion and other policies, those diminishing returns might be even more dramatic than we believe. Nosotros probably overshot on prison house construction years ago; 1 doubling might have been enough. Not simply should we cease adding prison capacity, but we might be meliorate off returning to the incarceration rates nosotros reached in the mid-'80s.

So this is the choice before u.s.a.: We tin either assail crime at its root by getting rid of the remaining pb in our environment, or nosotros tin can continue our current policy of waiting 20 years and then locking upwardly all the lead-poisoned kids who accept turned into criminals. There's e'er an alibi not to spend more coin on a policy as tedious-sounding as lead abatement—budgets are tight, and enquiry on a problem as circuitous as crime will never exist definitive—but the association between lead and crime has, in recent years, get pretty overwhelming. If y'all gave me the choice, right now, of spending $20 billion less on prisons and cops and spending $20 billion more on getting rid of pb, I'd take the bargain in a heartbeat. Not only would solving our lead trouble do more than whatever prison house to reduce our law-breaking problem, information technology would produce smarter, better-adjusted kids in the bargain. In that location'due south nothing partisan nigh this, nothing that should entreatment more to one group than another. It's but mutual sense. Cleaning up the residual of the pb that remains in our environment could turn out to be the cheapest, almost effective crime prevention tool we accept. And nosotros could first doing it tomorrow.

Back up for this story was provided by a grant from the Puffin Foundation Investigative Journalism Project.

Source: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2016/02/lead-exposure-gasoline-crime-increase-children-health/

0 Response to "Violent Us Crime Drops Again Reaches 1970s Level Fb"

Post a Comment